The Codebreakers

Earlier this year, we visited Bletchley Park. A trip long overdue, considering that we live some 30 Minutes away!

I was not quite sure what to expect – apart from ‘the battle against the machines’ of course – and I had no idea at all how powerfully this place would resonate with me. And it still does.

It was in the opening exhibition dedicated to codes and ciphers in wartime communication, when I realised that this place is, first and foremost, about people. The ‘work tools’ on display – the decoding stencils, handwritten notes and transcripts, files, and logbooks – they all spoke of meticulous, exhaustive work. Yes, it was the time when ‘cut and paste’ meant scissors and glue!

Further on, personal items such as hand-knitted mitts, scarves, cardigans and hats, pipes, ashtrays, pencils and notepads, telling reminders of the conditions the codebreakers worked in – in the dim, confined and spartan huts – producing ultra-intelligence that it said to have shortened the WWII by several years.

Further on, personal items such as hand-knitted mitts, scarves, cardigans and hats, pipes, ashtrays, pencils and notepads, telling reminders of the conditions the codebreakers worked in – in the dim, confined and spartan huts – producing ultra-intelligence that it said to have shortened the WWII by several years.

And afterwards, there was silence.

When the operation at Bletchley Park closed in 1946, the codebreakers packed their belongings and left and returned to their lives, not being allowed to share even within their closest families what it was they were doing there; all information about the operation in Bletchley Park was classified until mid-1970s.

It was such a humbling and emotional experience! These days – and I am certain this applies to both pre- and after the lockdown – we take so much for granted; we feel entitled. Our experiences seem non-existent until shared and acknowledged (read liked) on social media.

It certainly helped me to put things into perspective.

Back home, I decided to find out more about the people of Bletchley Park. As a linguist and practising translator, I felt professional pride and connection to the linguists at Bletchley Park, who were of such importance for the success of the operation.

That is hardly surprising though. I was intrigued what other professionals were there.

At the beginning, the recruitment aimed at ‘Cambridge and Oxford professor types’, and the list of academics indeed contains a historian, a mathematician, an Egyptologist, a logician, and an astronomer. As the operation grew, Bletchley Park welcomed a fascinating mix of professions from different walks of life. As one would expect, there were cryptologists, cryptanalysts, as well as military, naval and intelligence officers. And of course, technical talent such as engineers and topologists.

Interestingly, there were also many creatives – artists, writers, designers, biographers, a poet, a garden and landscaping historian, a journalist, an actress, a composer, a radio dramatist. Also, a solicitor, a schoolteacher, and a philatelist. Not to forget several chess players and chess champions.

What a fascinating mix of skill and talent!

It was only a natural next step that I wanted to find out whether there were any Czechs (or Slovaks) at Bletchley Park at all.

And this is how I found her!

Dorothea Karoline Fuhrmann was born in 1917 in Brno, Czechia, into a wealthy Jewish family of textile manufacturers.

When her parents divorced in mid-1920s, Dorothea and her brother Robert relocated with their mother to Vienna, where she began training as a theatre designer at Kunstgewerbeschule. Their father was the only member of the family to remain in Brno, and later died in Auschwitz.

In 1938, Germany annexed Austria. At that time, Dorothea designed stage decorations for the production of Midsummer Night’s Dream, but when she arrived in the theatre for the opening night, the notice on the entrance door said: No Jews.

She never saw her work on the stage.

Dorothea fled to London, which was only possible because she had a Czech passport thus did not need the permission from the Nazi regime to travel.

She continued her studies at the Reimann School in London, but then the WWII intervened.

Dorothea joined the WRNS (Women’s Royal Naval Service, known as the WRENS) and because she spoke foreign languages, she became a radio intelligence officer (‘the listener’). She intercepted coded messages from the German naval forces, thus becoming key part of the broader Bletchley Park Operation.

In 1940 she married Leonard Klatzow, a South African physicist, who tragically died in 1942 in a plane crash.

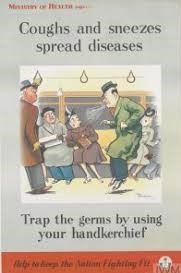

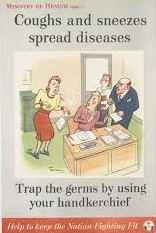

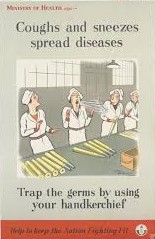

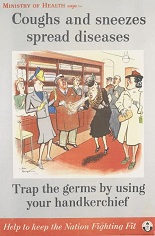

After the WWII, Dorothea pursued her career as a designer and worked at the design studio of the Central Office for Information, producing government campaign posters, amongst other the famous ‘Coughs and Sneezes Spread Diseases’:

This is when she created her professional name: once asked to sign her artwork, she realised that both her maiden and married names were too difficult to recognise in the UK, decided to use her initials D.K.K. instead and created herself a professional name – Dorrit Dekk. Her mother, a Dickens enthusiast, has always called her Dorrit.

After a brief interlude in Cape Town, she returned to London in 1950 and established herself as a freelance designer, printmaker, and painter.

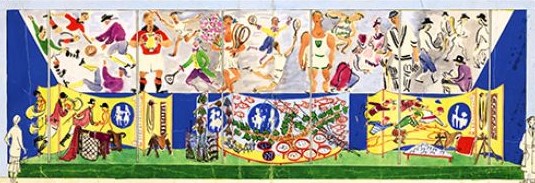

The milestone commission was a design for the Travelling Section of the Festival of Britain in 1951, a national exhibition and fair that attracted millions of visitors across the UK. Dorrit created a mural representing popular British sports, games and pastimes called People at Play.

With this piece of work, Dorrit entered the British design world. She has always been proud to be part of the 1951 festival.

She gradually built her own successful design practice and in 1956, she became a fellow of the Society of Industrial Artists (today Chartered Society of Designers).

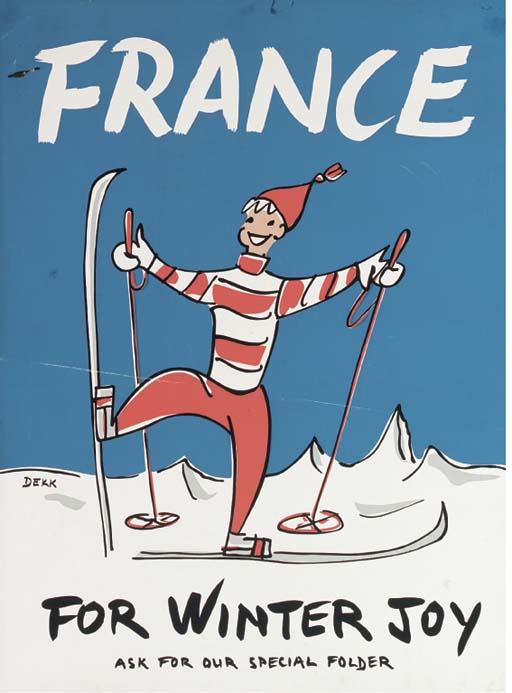

Dorrit became known as the ‘travel queen’ through her work for Air France and P&O. However her work spanned from book covers and illustrations (Penguin and The Tatler were her clients) to advertising for London Transport, British Rail and Post Office savings bank. She considered herself art designer rather than fine artist.

Dorrit became known as the ‘travel queen’ through her work for Air France and P&O. However her work spanned from book covers and illustrations (Penguin and The Tatler were her clients) to advertising for London Transport, British Rail and Post Office savings bank. She considered herself art designer rather than fine artist.

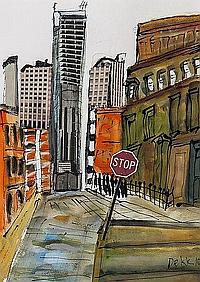

Dorrit Dekk became one of the most influential and successful commercial graphic designers in the post-war UK. Her main medium was collage which she used in her posters as well as paintings. For her quirky landscapes and urban scenes she used gouache.

She continued to create pieces of abstract and figurative art as well as her favourite collages even after a stroke she suffered in 2001. Housebound and on a wheelchair, she enjoyed receiving young students of art in her studio, for whom she was an admired role model. Famous for her eccentric stripy socks, and loved for her infectious spirit, her passion for all things art and architecture, and for her sharp wit, Dorrit Dekk was one of a kind. She died in London in 2014 at the age of 97.

■■■■■

What a journey, what an unexpected discovery! Little did I know that a day’s trip to Bletchley Park will lead me to discover this connection to my hometown Brno, and that I will get the opportunity to ‘meet’ Dorrit Dekk, a brilliant artist and a beautiful person, in and out. I look forward to continuing learning about Dorrit’s career and art, and about her full, eventful life. She was a true fighter; in her own words, she seemed to be completely indestructible!