A Tale of a Vanished Poet

Ivan Blatný was born in 1919 in Brno, Czechoslovakia. In his twenties, he was alrady one of the central figures in the cultural avant-garde. He published four books of poetry and two books of poetry for children before he turned thirty. He left Czechoslovakia shortly after the communist coup d’etat in 1948, for a cultural exchange organised by the British Council. On his first night in England, he announced on the BBC that he would not return home, because of the new regime. First came a fury and a hateful campaign against him.

And then, silence.

His name became taboo, his poetry was blacklisted, he was stripped of his citizenship and for the official culture, he was as much as dead. One of the most celebrated young poets of the generation became a non-person. His name was erased from the Czech literature and was meant to be forgotten forever.

The silence lasted for 28 years.

Only his family and closest circle of friends knew his whereabouts, and even those ties gradually faded because of lack of contact.

It was only months after he settled in England that he was hospitalised for mental illness for the first time, although he briefly worked as a journalist for the BBC and Radio Free Europe.

He th en spent most of the time until his death in various institutions, although it is not even clear whether he needed therapy for specific diagnoses, or whether he was primarily seeking refuge from life ‚out there‘ that became unbearable.

en spent most of the time until his death in various institutions, although it is not even clear whether he needed therapy for specific diagnoses, or whether he was primarily seeking refuge from life ‚out there‘ that became unbearable.

His cousin Dr. Jan Šmarda secretly visited Blatný in 1969, in the brief period of Czechoslovakia‘s reopening. In the same year, a secondary-school teacher from Brno Vladimír Bařina visited him too. He was an admirer of Blatný’s work.

Most of Ivan Blatný’s life in England remains a mystery though, and many questions unanswered.

The personnel knew him as a quiet, lonely man, who hardly ever spoke to anyone, and who spent whole days staring at the wall, or tirelessly scribbling on loose sheets of paper provided to him – it was thought therapeutic. Nobody could ever decipher his scribbles, thought to be in some made up language; not that they cared to, he was a psychiatric patient after all, and quantities of those papers were discarded for hygienic reasons.

Until one person cared.

At this point, we should perhaps rename our story to ‚A Tale of the Nurse and the Poet‘.

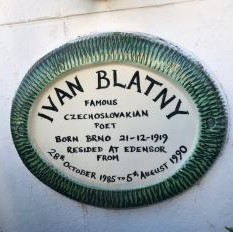

Miss Frances Meacham was a nurse at St. Clement’s Hospital in Ipswich, where Ivan Blatný was transferred to in January 1977.

Since school years, Frances Meacham did not care much for poetry. She did not speak any foreign languages either. But she had a connection to Czechoslovakia since WWII, when she served in the Royal Air Force medical corps as part of the Czechoslovak brigade.

After the war, she kept contacts with many friends, ex-patients and, in her own words, ‘marvellous people she got to know in this wonderful country’. And once she even visited Czechoslovakia, Brno more specifically, to see a friend who had served with her in WWII.

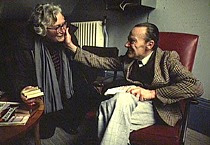

By pure chance, she met Vladimír Bařina who told her about his friend, a patient in the very hospital where she worked as a nurse. Frances Beacham was moved by the story and when she returned home, she went to see the man she learnt about.

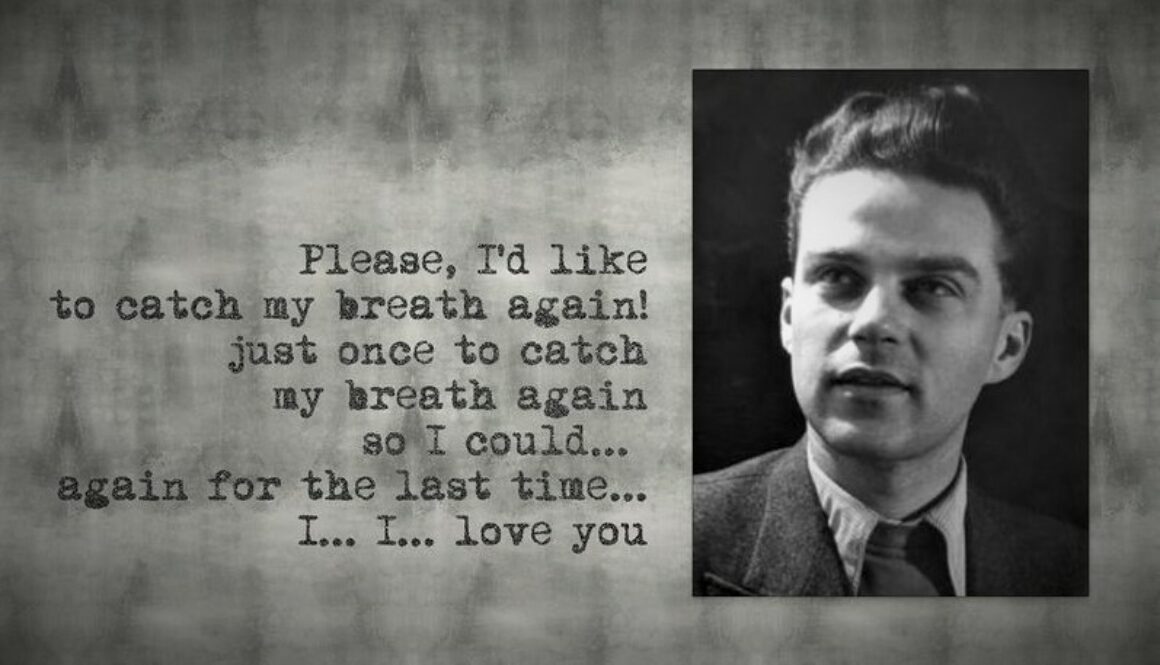

Despite her colleagues’ discouragement, she gradually managed to bring him out of his silent monotony. He confided in her that he used to do a bit of writing, and still does at times, but that the nurses always throw everything away. Whatever was left of his work, was in a folder of sheets full of his scribblings, hidden in a drawer, that somehow escaped the nurses’ attention. He trusted Frances and let her look at them.

She took everything home with her and the next day, she brought fresh supply of paper. She told the management that the man used to be a famous Czech poet. She made them promise that they will not throw away any more of his scribbles and asked them to give him a typewriter. She photocopied the manuscripts and sent them to Canada, to another Czechoslovak émigré, a great novelist Josef Škvorecký.

Škvorecký replied immediately: ‘Please send me everything he has written.’

He knew immediately, whose work he was looking at, and realized that the poet, long thought deceased, was still writing beautiful, melodical poems.

A first collection of selected poems was published. The book (several copies were sent to the hospital) finally had persuaded the physicians at St. Clement’s that their patient indeed was a real poet, and he was allocated a private room and a typewriter.

And so, the man, who at a terrible personal cost became a total poet, a walking and breathing organ of poetry, has finally had his name returned to him: Ivan Blatný, poet.

Thank you Miss Meacham!

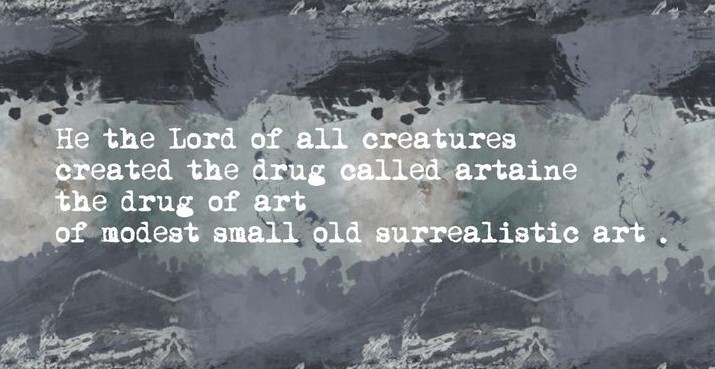

A book of selected Blatný’s poems ‘The Drug of Art’ – with both Czech and English versions:

ISBN 987-1-933254-16-6

For further reading, listening and reference:

https://english.radio.cz/ivan-blatny-strange-story-a-czech-poet-english-exile-8083530

https://www.mujrozhlas.cz/auditorium/1990-zemrel-ivan-blatny

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228608534059

http://thelondondead.blogspot.com/2017/05/quite-decent-mr-kozderka-astonishing.html